You are currently browsing the tag archive for the ‘travel’ tag.

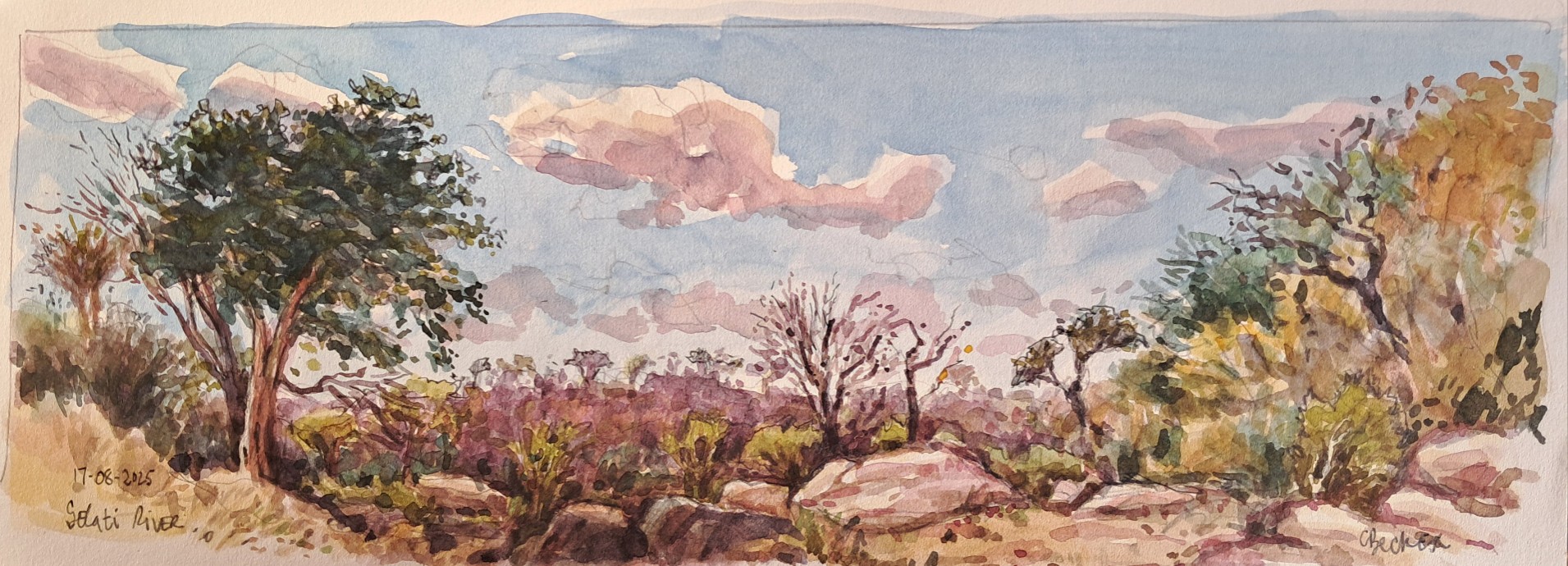

By a stroke of good fortune, I’ve again escaped the dank and stormy Western Cape. I’m in the Selati Nature Reserve, not that far from the Kruger Park. Right below our lodge runs the Selati River. OK, it’s not exactly running – but there are large pools of water just below the lodge, and these are often visited by Kudu, Impala, small antelope and many birds. The bushveld in winter is another story – perfectly warm windless days, followed by cool, crisp nights around the fire. The beautiful Nyala are almost tame and spend their days browsing around the lodge. They will obligingly linger long enough for a quick sketch.

Our lodge isn’t fenced, meaning, yes, we could cross paths with wandering predators or ruminants at any time. Crossing the lawn at night we feel a primitive frisson of fear. Things are rustling in the undergrowth, and we can hear the throaty cough of a lion. Sound carries far in the still night air, but how far away is it, exactly? Are we being watched? Are we being crept up on? In the enveloping darkness we stare into the hardwood coals of the bushveld braai fire just like our ancestors did, frequently scanning the perimeter for yellow eyes. We’re comfortable but, like those ancestors, aware that something just might be seeing us as food. We find ourselves in a relaxed but ready equilibrium, and it feels good.

In the morning I wander down to the riverbed. The dryness of the earth is astounding, brittle grasses crunching underfoot. The colouration – mainly siennas and ochres – is right up my street. Fragrances of dung drift up from the warming earth. I’ve got watercolours and a small chair, and I set up on one of those huge granite boulders. There are intermittent shallow pools of water here and a kingfisher hovers and dives. Are there really fish in those pools? What is he catching? I know so little! Up river I see Impala and furtive Kudu flitting in and out of the shadows of the yellow Mopani trees. Could there be a better place than this? I paint because the slow, focussed, meditative act of painting is the best way I know to connect with this old world. But even in Arcadia things can go wrong, starting with dehydration and sunburn, and ending like this:

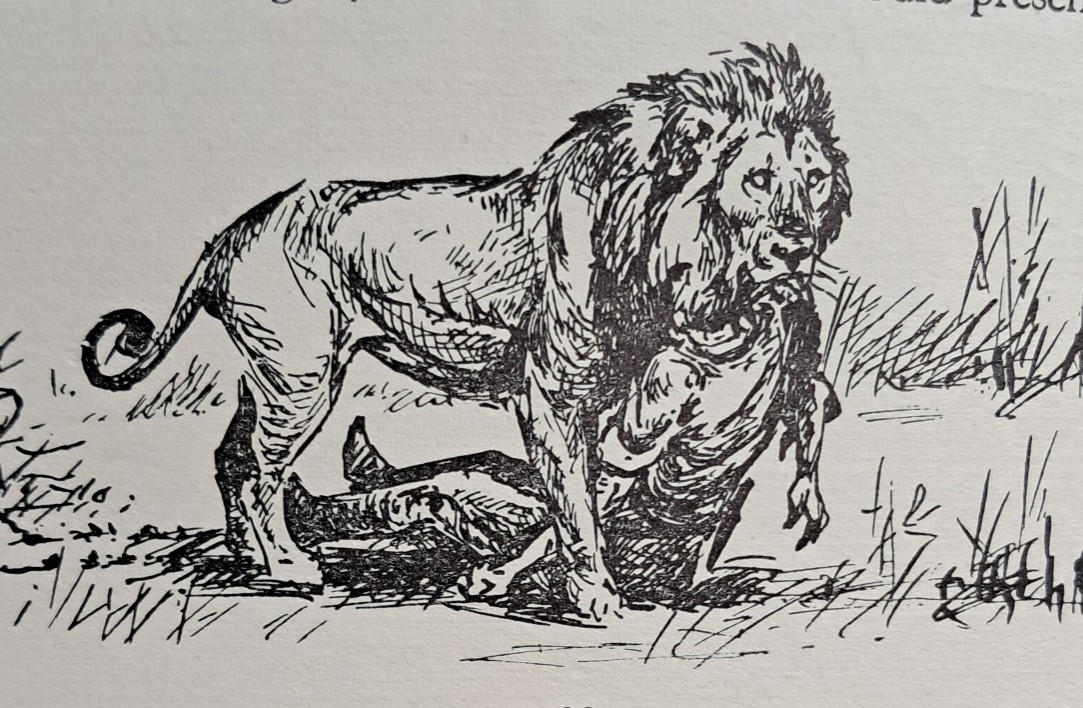

Incidentally, there are at least two survivors of lion attacks who lived to tell the tale. The steely and evangelical David Livingstone was one. He felt no pain, and reasoned that the shock of the attack had put him into a state where he could observe but didn’t feel. He hoped, he said, that all prey died in that state.

“I certainly was in a position to disagree emphatically with Dr Livingstone,” said Harry Wolhuter, one of the first game wardens at the Kruger Park. Wolhuter had been pulled off his horse, and the lion was dragging him along by the shoulder. “As the lion was walking over me, his claws would rip wounds in my arms…I was conscious of great physical agony; and in addition to this was the mental agony as to what the lion would presently do with me.” He had his sheath knife with him, and he managed to stab the lion in the heart. Then, in excruciating pain, he clambered one -armed up a tree and, ready to pass out from loss of blood, strapped himself to it. There were two lions, you see, and before long the other lion was hungrily eyeing him too. Eventually help arrived, and the next day, unable to walk, he was portered through the bush to Komatipoort hospital, a mere five day journey on foot. The pain and sepsis must have been incredible, but Hardy Harry survived this ordeal with all his limbs intact.

In the course of his duties, Harry Wolhuter shot a lot of lions. This seems strange – even shocking – to us, but in the early days of the park, there were very few antelope. The game had all been shot out by hunting, not to mention hungry Boer Commandos during the Anglo – Boer war. The only way to get the numbers up was to thin out the predators. So the lions, leopards and wild dogs had to go.

The wild I am seeing now looks primordial, the way it has always been and should remain. It is easy to forget that earlier generations saw it as hunting territory, as farm land, as bushveld that should be settled and subdued. Our attitude is now less extractive, more preservation, and of course it helps that tourism can be made to pay. But threats remain: poaching, mining, climate change. Fortunately there are dedicated individuals working to see that Arcadia lives on.

Lion attack illustration by the great CT Astley-Maberly. From Harry Wolhuter’s “Memories of a Game Ranger.”

And so to the West Coast for a short break from the rigours of life in the Overberg. It’s a family outing – the good doctor and new pup Cleo are on board. The open road lies ahead! My late aunt Gisela, a staunch Capetonian, never had anything good to say about the West Coast. As we traverse the outlying industrial wastes of Cape Town and the scorched earth wheatfields towards Malmesbury, I have to agree with her. Close to the West Cape nature reserve we catch sight of some giraffe leaning into the wind near the road. They strike me as anomalous, out of place. They should surely be browsing the leaves of tall acacias, not scrubbing it among the treeless fynbos. After all, it was only much closer to the Gariep River, way to the North, that Francois le Vaillant encountered his first Cameleopard, which he promptly shot and skinned. But I digress.

Fifteen kilometers before Paternoster is the town of Vredenburg. It is surprisingly large, the coastal equivalent of say Newcastle or Rustenburg, with an extensive, abject shack settlement rolling over the parched hills. Where did all these mense come from? What the hell are they doing there? Closer to Paternoster, there are clumps of huge rounded Stonehenge – type boulders jutting out of the earth, the only thing in sight for the eye to fix upon. Pods of sheep dot the barren wheatfields, while crows circle overhead. Never a good sign that, when crows are the only birdlife.

Coming in to Paternoster, there’s no “wow” moment, no indicator that we’ve entered the idyllic realm of fishing boats- on -the -beach, as depicted by many a local artist. Having brushed off several loud crayfish salesmen of the street, (Kreef! KREEFFF!!) we find ourselves in a comfortable flatlet, surrounded by white houses in a faux-mediterranean style. They have names like “Duintjie” and “Strandloper.” There’s a strict aesthetic conformity here. Voelklip, where I live, is an architectural calamity: kak facebrick houses, grandiose concrete bunkers, this and that. I’ve always thought strict aesthetic controls would have been a good idea but now I’m not so sure: this place looks too much like, well, a theme park. With old fishing boats strewn on every other corner to give it authenticity. The wind is blowing and yes, your aging artist sees nothing to sketch and is grumpy.

Next day, we find out a bit more about Paternoster. The original inhabitants, mainly coloured fisherfolk, woke up one day to find white people offering wads of cash for their cottages. They took the cash and next thing they were on the street with large nouveau- Greek houses going up around them. Fancy eateries too. ( Kreef! KREEFF!!) But the fisherfolk smartened up and stopped selling their houses. So now, uniquely in South Africa, there’s an interesting mix of class and culture, as the rich bastards are cheek by jowl with the hardscrabble fisherfolk. Across the way from the Paternoster Hotel, (an authentic – looking place, by the way,) there’s a group of Kreef sellers. They gather every morning under the shade of the bloekombome. It is thirsty work on these hot summer days, and the manne keep quarts of beer close at hand. They joke and jest loudly, en hulle vloek mekaar lekker. I did a little sketch of that scene, thinking that a real artist would go right in there and do a series of portraits of those fellows. Francois Krige, perhaps, would have risen to the occasion.

There’s a Paternoster waterfront, better than the Cape Town one. It’s a warm day but under the shade it’s just right and, surrendering to the boats -on-the-beach cliche, I get on with a little watercolour. I’m working on 300g hot pressed paper and mixing in a bit of gouache. My painting gear is simple and portable: everything I need fits in the satchel. The sea is flat and iridescent and there are those beautiful big luminous rocks out there. The sculptor Henry Moore would have cried to see those. Everyone here is relaxed and in browsing mode, so I get several onlookers. I’m happy to interact with them and hear their stories. I meet a man from Namibia who is finding his extended family who came from the West Coast. Also a few watercolourists from England. They are polite and encouraging. I’ll take any morale – booster. After all, plein – air work is mostly destined to fail and disillusion always lurks. There is a German man too. ” Ah, malerei,” he says, surveying my handiwork. ” Ja, very good. Und such a light equipment too.” How very Teutonic, to asses the means as well as the result! Thanks my broer. We live to paint another day…..

Portjie pic

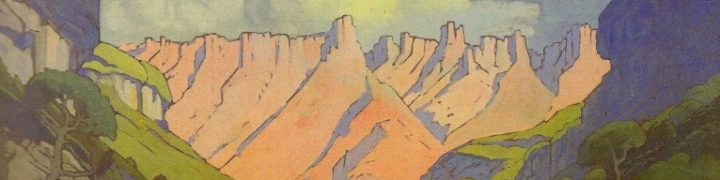

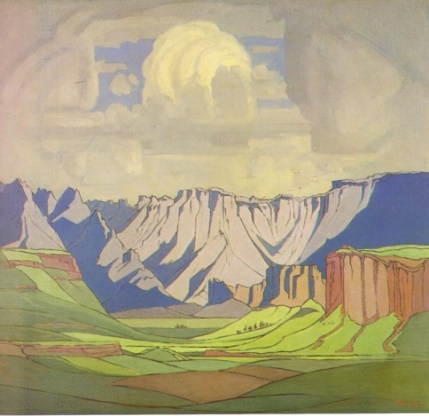

And so, Northwards, to Namibia! First though, to the Caledon Home Affairs office, to collect my new passport. There was one stamp in my old passport, an entrance to Lesotho at the Maputsoe bridge. That was my first crossing into a foreign country in search of Pierneef, many Octobers ago. So, indulge me dear reader while I tell you about this little excursion.

The Lesotho site has proved the most elusive of all the 28. There’ve been many “direct hits” and many other places where we sense we’re in the general ballpark. But Lesotho? I’ve driven all the way around the Western flank, more than once. Clearly, Pierneef gazed at the Maloti mountains from somewhere in the Eastern Free State. I bet on Ficksburg because Pierneef had spent some time there in 1922, doing mural paintings at the Hoerskool. I found a helpful bloke in the Ficksburg tourism office, and after much consideration, he decided this view was actually inside Lesotho. He took out a map and marked the route there for me: along the R25 towards Katse Dam, just past the village of Pitseng. That’s where I’d find it. So now the search had become transnational. On the other side of the border I bought a stout walking stick, beautifully beaded at one end. Good for klapping your enemies or to lean on when ascending the mountain slopes.

I drove windingly past scattered settlements, nestled against the slopes in a pleasing way. There’s a happy confluence of traditional and more modern-looking houses. Cars, livestock, poultry, and pedestrians all share the roadside and the whole thing seems to tick over at a leisurely egalitarian pace.

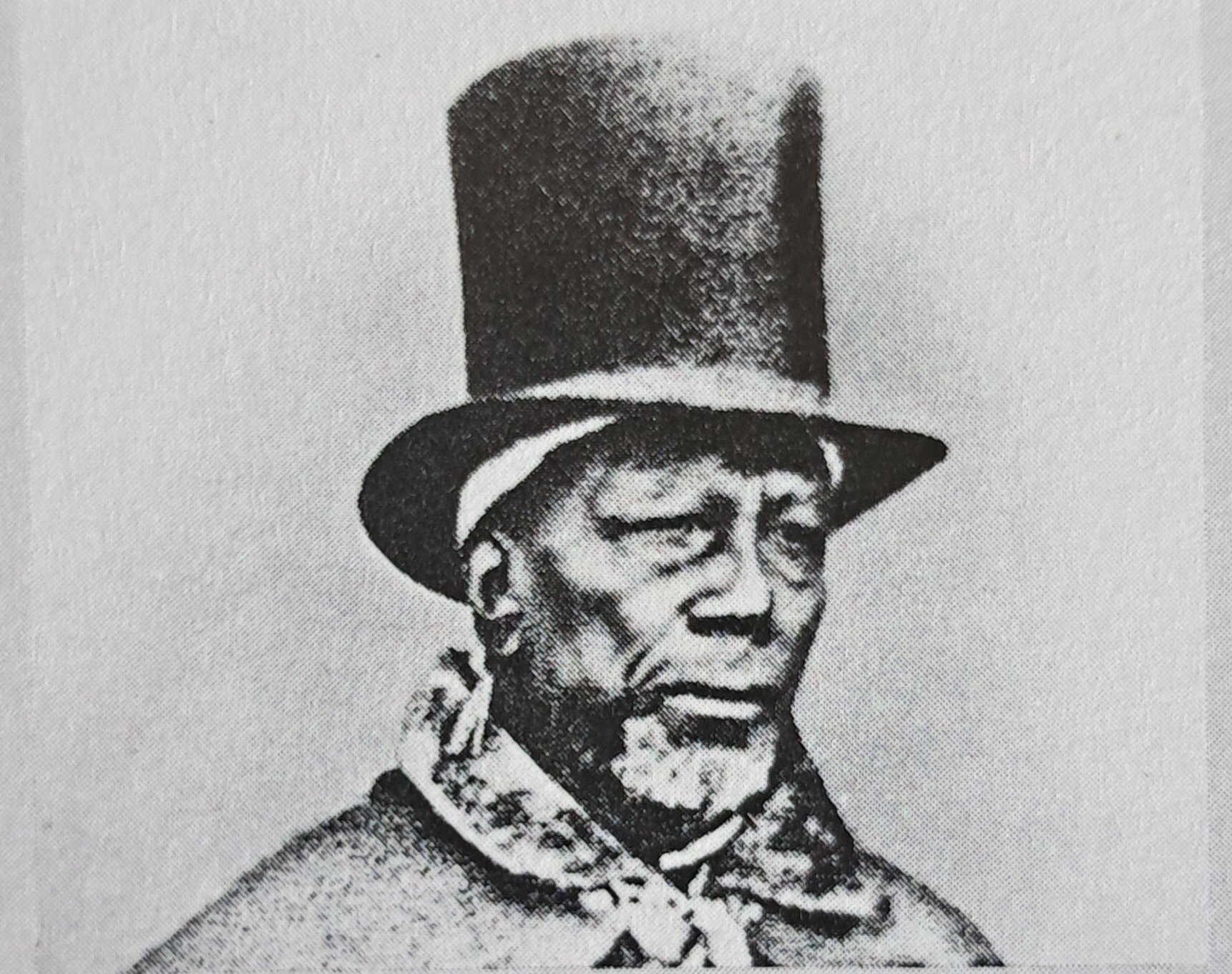

I went into a small supermarket and the teller, delighted to have a tourist, pointed out the grand figure of “our Father, Moshesh” on the banknotes. In the mid 1800s, Mosheshwe took a bunch of desperate, dissolute refugees and shaped them into the Basotho nation, while fighting off the likes of the Mantatees and the Boers from his mountain stronghold of Thaba Bosiu. He was one of the greatest Southern Africans.

I got to the village of Pitseng. Nothing remotely looking like Pierneef’s painting. I went on further towards the Katse dam, getting into the high country. It wasn’t right – I was supposed to be looking at the mountains from afar. I did a sketch and turned back, stopping for a quick little drawing of houses.

Unable to resist a dirt road, I took a detour. There wasn’t that much of the day left, and I knew that I wasn’t going to find the site.

On the barren road I met the children of Moshesh, brightly dressed against the khaki landscape. They were happy to strike a pose.

Later, getting back on the main road, I met a man carrying a small white wooden suitcase. He said, ” Are you perhaps interested in some of Lesotho’s finest?” Stupidly I thought he was referring to the hand -crafted suitcase, but when I looked inside, it was full of well-packaged dagga. A traveling salesman! I politely declined, but perhaps I few drags on the dagga cigarette would have helped put me in touch with the ancestors, who could have guided me to the Pierneef site? Ja Nee….