You are currently browsing the tag archive for the ‘Carl Becker artist’ tag.

Kimberley. Not really known as an art epicentre. But wait, in the middle of town there’s the William Humphreys Gallery, one of the country’s finest public art institutions. Your blogger was there in July, showing off his latest work, and I tell you it was good. Under the hand of curator Ann Pretorius, the gallery has assembled a superb permanent collection. There’s a tea- room in a garden which is home to quite a few feral cats, as well as a statue of Queen Victoria. She stares determinedly at the palisade fence, a grandiose relic of a grandiose time. The passing students of Sol Plaatjie university pay Her not the slightest notice.

a tot of Laudanum, anyone?

Approaching Kimberley from the south, you drive through bushveld with many beautiful thorn trees and historic battle sites. After just a little bit of semi- industrial stuff, you’re right in the town. A town that has a lot of history etched into it. This is where South Africa met Modernity. A vast onrushing money -grabbing multinational mob was unleashed right here on the arid plains, and the old pastoral country was dead and buried. Some of that mob did very well for themselves, leaving us some splendid homes to look at, like these in Carrington road.

What is it about these houses? I think they’re marvellous, perfect in every way. So much better than the concrete bunkers favoured by today’s well-to-do. Glance downwards, and the paving stones are carved granite. There they are in the picture above. Hand carved granite paving stones! Not messing around then, your colonial-era road builders.They were in it for the long haul, thinking Remain, definitely. Near the CBD, I found this architectural oddity:

It comes complete with a trashed -out parking lot, and where are the windows? What would a future civilisation make of this edifice? Will they think it a temple to strange gods, the gods of small bright stones? A place where pale-skinned initiates peered for hours at the stones, in rooms without north-facing windows?

After the exhibition opening, we went to the Kimberley Club for a late and large supper. There are ghosts of a former world here, notably bad-hearted Cecil Rhodes. He lurks in the garden, warily keeping an eye on the door. These days, no doubt, new elites are hatching schemes and cutting deals at the same old bar, whiskies in hand. Coming out of the Club, I took a wrong turn and briefly went on a late-night drive through the CBD. For a little while I was lost and suddenly alone in the empty litter -strewn streets. I confess, a primal child- like tightening in the chest crept up on me. Then I came across a gang of black men repairing the road outside the town hall.

Which way to Du ToitsPan road? I asked.

Ons praat nie Engels nie, praat Afrikaans! said they.

I passed a shebeen along the way. Loud and clear, the sounds of Elvis’s Blue Suede Shoes belted forth out of the darkness. I’m still trying to figure that out, that burst of rockabilly music where I never thought I’d find it.

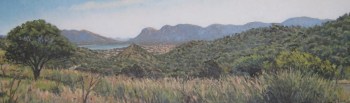

Yes, it is a mere 5 months since my last posting, dear reader. I had an acute dose of blogophobia, which persisted despite the mutterings of my irascible blog coach. It took a visit from Monique Pelser to shake me out of my lethargy. We met in 2009, and by a remarkable coincidence, found that we had both been to the Pierneef Museum in 2006 and decided to follow his footsteps. It’s unsettling when someone else has also had your big idea, but we opted for co-operation rather than competition and so Pelser and I are going to be exhibiting together at the Stellenbosch University Gallery in April. Between us we’ve been to 27 of the 28 Station Panel sites, so its going to be a comprehensive show, with the photographs and paintings suggesting different ways of interpreting the landscape. The old harbour in my home town of Hermanus is one of the Pierneef sites, and Monique came out to photograph it last week.

You’ll notice how Pierneef enlarged the buildings. He took a close up view of them and pasted it onto the view of the mountains. You’d have to be suspended in mid air to get a photo of that. Monique’s solution to the multiple perspectives often found in the Station Panels has been to use two cameras angled away from each other to give us an extended view of the sites. Painting and drawing outside, Pierneef would have spent many hours there. Today we tend to point and click and be on our way. We experience the landscape in soundbites and as a result we miss a lot. So Monique has chosen to immerse herself in the landscape. She sets up her cameras at dawn and, taking a picture every five minutes, stays at the site until sunset. These “photo sketches” are then projected onto a screen, giving us a remarkable record of a site over a day. To be viewed properly, the viewer has to give up their time, as if the photographer is urging us to put our own frenetic lives on hold to consider something bigger than ourselves. We may just find it was worth the wait.

1. It is 1998. The painter is on a dusty Karoo road. He is driving an old kombi, the map book lying open on the floor behind him. There is a boy with a dog on the road. The painter gives them a lift to a farm many kilometres away. Later, at home in Jo’burg, the map book falls open. On a page, there is a paw print left in dried blood. The painter remembers the dog.

2. The painter is on the road between Whittlesea and Aberdeen. The trivia of everyday life starts to dissipate and he feels his soul expanding into those large spaces. It is 10.30 am, the time he usually takes his dog for a small walk around the corner. He pictures the dog at home, curled up and alone.

3. The painter has a dog at last. He is visited by a friend, a prolific artist and painter of many dog portraits, including Paris Hilton’s dog, no less. He comments on the fine form of the beast and takes a photograph. He says she would make a fine subject for a painting. In order to avoid the ignominy of having his dog painted by another artist, the painter makes a work of her.

4. Pierneef’s home in Pretoria. Called Elangeni (place of the sun), it was built in the late 30s using stone and thatch from the area. Sad to say, the pic was taken after Pierneef’s death and so we don’t know who that mutt on the left belonged to. But I have no doubt he would have approved of the Africanis on the basis of its indigenous aesthetic appeal.

The September exhibition date looms. Many of the chickens have come to roost at one end of the studio, quietly bothering me. The painter Simon Stone was once asked “when is a painting finished?” “When it stops irritating me ” was his answer. The business of finishing is just that, a slow burnishing away of faults.

The square ones at the top are 20cmx20cm – part of a set of twenty. The bottom row of paintings are an old standard size: 9×12 inches. They’re done on Belgian linen, made up in Jo’burg about seven years ago. At last, the right moment and the courage to paint on them! Belgian linen is the holy grail of paint surfaces (particularly oil primed BL).

Mostly, when a work goes as “oil on canvas”, it is something called “cotton duck”, an inexpensive and durable support, but not as smooth as BL. It’s only when you’re really making good money that you’ll be ordering Belgian linen from your canvas makers (as Robert Hodgins unfailingly did). Meanwhile I’ve had a bad run of it with canvas suppliers, so I’ve resorted to stretching a few of my own. For the first time in about 15 years.

You need a stapler and, unless you have a particularly strong pair of thumbs, a purpose built canvas gripper. This is a good thing to do on a Saturday afternoon. I recommend the boeremusiek programme on RSG as audio accompaniment, but that is optional. The trick is to get it stretched tight, but not too tight. You should only take tea whilst doing this. Definitely no liquor. That will count against you when it comes to the folds on the corners.

With that behind me, I still had the problem of wanting more small Belgian linen canvases to work on. (You get addicted to the feeling of the brush gliding effortlessly over the surface, you understand.) My quest took me to The Italian Shop in Rondebosch. The proprietor, Angus Kennedy, is a mine of information and an hour later I left clutching the beautifully made up 9×12 linens as well as a whole lot of stuff I hadn’t really thought I’d be buying. Like this beautiful 60ml tube of artist’s quality Cadmium Red from Maimeri. At R360 a tube, I rate this a buy. You can get through a lot of 9×12 size canvases before you squeeze out the last bit of this pigment.

I’m doing a biggish oil of the Hermanus site – it consists of seven small images. After three days I had three small images in place. Like a happy construction manager I was even figuring how many more hours it would be before the painting was done. But by day four, things suddenly started to look wrong. The canvas was cluttered and kind of formulaic in its intention. The thing that Hemingway called the “crap detector” was starting to ring, and I had to press the Delete button. Day one, two and three’s efforts were painted over. Day four’s too. It wasn’t their fault. They were just in the wrong place at the wrong time. But I’m giving one of them a second life:

The saying “to walk the line” originates in the American Midwest. In the days of railway construction, parched and hungry construction workers would walk the line for miles, checking that all the beams were in place. Ahem. Your crap detector should be warming up now. I have no idea where it comes from. But it’s a good way of describing the need to make aesthetic or other judgement calls. And I’ll let you know how the big one turns out…

Despite the charm of the house, I headed back onto the highway with a vague sense of loss. My conversation with Hans wasn’t all that optimistic, to tell you the truth. He doesn’t share his grandfather’s sense of permanence. He feels his children’s future may lie elsewhere, perhaps out of Africa. And then, cutting into the lane in front of me, my subject appeared. It was a little dented and moving quite fast.

The minibus is not known for its respect for the rules of the road. To your average whitey, the minibus represents the End of The World As We Know It. Over the years, I’ve rendered a few of them. Initially it was a way of neutralising an irritant. (Painting can do this, for the artist and the viewer.) Later it became another little pathway to acceptance. In the Fordsburg studio though, the din from the hooting taxi could stretch your tolerance. Torrents of abuse would flow from the balcony onto Main Street. Sometimes the artists were known to flick paint from their brushes onto the offenders below.

Once, sketching at a taxi rank in the Jo’burg CBD, a man stood behind me and watched me draw. “Eish! You can say that is dangerous!” said he. I never worked out if he meant the drawing or the taxi. But I like the idea of a dangerous drawing. And the thing is, now that these dangerous little vehicles are being replaced by those lumbering high roofed ones, they’ve acquired a certain sentimental value. They’re becoming relics, symbols of an era. Rather like a Pierneef painting.

The year rolls gently to a close. Your blogger has been laid up with a touch of summer influenza. Not an altogether unpleasant experience, dozing off while outside the wind brings in some overdue rain.

I’ve been ploughing through Denys Reitz’s superb trilogy, Adrift on the Open Veld. Commando is the classic memoir of the Boer War. And his subsequent soldierings through East and West Africa and the First World War are a vivid account of hell, breezed through in high spirits. Later, as a Member of Parliament, Reitz travelled widely in SA and there were frequent political meetings on the platteland. These often ended – or began – in fisticuffs, heckling and chair throwing, such was the enmity between Jan Smuts’ followers and General Hertzog’s fervent Afrikaner Nationalists. Does this ring any bells, COPE, ANCYL etc? Finding the present reflected in the past is comforting. In this case at least, we continue a proud tradition of misbehaviour.

As the nation prostrates itself beneath the sun, we get a break from the deal makers and turf pissers who so vocally thrust themselves into our psychic space. You know the ones. There’s a brief lull as they emerge from their tinted German sedans to sun themselves. Enjoy it while you can, for they shall be back…

Of course, finding these sites means I can see what Pierneef had in front of him. But I also have the chance to see the 360 degree view, to see what got left out. On my right at Rustenburg Kloof there are modest kuierplekkies. They look like they’re from the late fifties or early 60s.

There are also facebrick dwellings from the 70s or 80s, ok, but not very attractive. I notice they’re occupied not by your customary paleskinned weekenders, but by black okes wearing bright yellow T-shirts with trade union logos. The kind of people the white braaivles people used to put in jail. Straight ahead, in exactly the spot where Pierneef put that grand thorn tree, there is a little building. It looks like a change room perhaps.

They are also in a kind of a sixties style, but they’re crumbling. A bit like the Pelindaba parking lot. The young patriots that used to come out here to hike and swim in the river have all grown and up and gone to work in Canada. But these aren’t the first regime changes these cliffs have seen. In his memoirs of the Boer War, Jan Smuts writes eloquently of the Magaliesberg, of the carnage and change that war brought to these valleys. He recalls how the original inhabitants, called the Magatse, were ruthlessly slaughtered by Mzilikazi’s invading hordes and concludes: “Truly the spirit that broods over Magaliesberg is one of profound pathos and melancholy….I had borne in upon me as never before that haunting melancholy of nature, that subtle appeal to be at rest and cease from the futility of striving.”

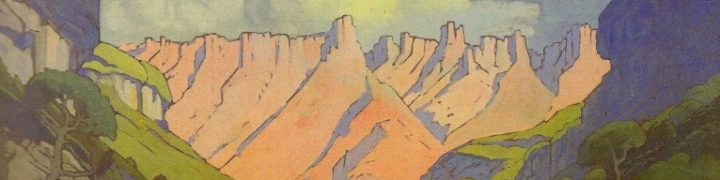

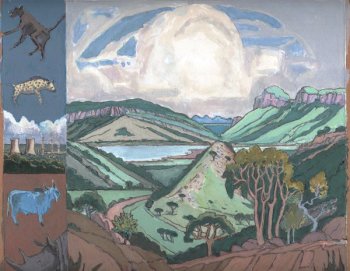

A little to the West of the platinum boomtown is the fabled Rustenburg Kloof. This is a popular picnic site and Plesieroord, where the lawns around the 60’s style bungalows are well watered and trimmed. Knowing the site from my own reworkings of the original Pierneef, I found the exact spot right away. Of all 28 Station Panels, Rustenburg Kloof may just be the best. The Pierneefian formula of a melancholic landscape underneath huge building clouds can get too obvious at times, but here it is very strong.

Careful, mathematical composition is a hallmark of the panels. They’re also very strongly circular – the arch of the clouds finds an echo in the ochre earth. The circle is reinforced by the use of tone – so we are drawn to the centre by that very light Naples yellow behind the thorn tree. Also, the cliff seems immense behind the contours of the central dark areas – there’s no middle ground to give us a sense of its scale.

That bit of tarmac covers a small bridge running over the river, barely discernable in the original on the left. The tree to the left may or may not have been there 80 years ago. Either way, he chose to put in a thorn tree instead. In the late morning light, it looks good but ordinary compared to the high drama of the Pierneef. The afternoon light above the rockface makes it look craggy and pitted – nothing like that smooth expanse of rock in the painting. The Pierneef is based on an early morning light. And you wouldn’t see those clouds early in the day. Aha, another of Oom Henk’s little manipulations.

We take it for granted that the camera shows us what is “real”. But it only captures a moment. Pierneef gives us a highly stylised version of the world, but it conveys a reality far truer to our memory and our emotional recall of the South African landscape.

The Hartbeespoort Dam Station Panel.

The Hartbeespoort Dam Station Panel.

I found this site easily enough. It’s on the R514 as you head towards the dam. The day I was there (for I am not there now, dear reader) was the end of a long weekend and the whole of fun seeking Gauteng was roaring back to Egoli with boats, bikes, caravans and jetskis in tow. Nevertheless, I put on the suntan lotion and got down to work. The noise coming up from the road started pissing me off after a while, but in the stolen quiet moments I realised The Thing, and that is that what Henk had before him was Nirvana, no less, and that we, in our headlong rush toward comfort, acquisition and consumption, are screwing it up. Behind the rash of Tuscan townhouses that ring the Dam, the water glows an eerie green. Cyanobacteria – a malevolent and toxic algae – flourishes in this sewage laden water. You wouldn’t really want to go waterskiing there.

It was in a nearby hotel that Pierneef was to meet his second wife. It’s been noted that around that time, too, his work and career began to flourish. The stabilising influence of a good woman on the daydreaming artist, no doubt.

I met a woman last year who had rented one of the rondavels at the Pierneef’s Pretoria home in the 1940s. The young couple admired Pierneef’s work, and, at one of his home exhibitions, scraped together the money to buy one of his watercolours. But, announcing that “Henk’s paintings must only hang in the finest homes in Pretoria,” Mrs P cancelled the sale. Eina.

Over the hill and through the deserted Pelindaba parking lot.

Nature creeping into the cracks in the tarmac left by retreating Nuclear geeks. In his book “Of warriors, lovers and prophets,” Max du Preez tells us that the name Pelindaba means the debate (or problem) is finished. An atom bomb would be a good way of closing an argument, it’s true. But for now the argument is kind of shut down while we work on new Nationalisms and new debates. Across the Hartebeespoort Dam wall there are a whole lot of interesting businesses on the go. Next to the curio, fruit and sunglass vendors, large African animals proliferate.

Kind of better than a stuffed rhino, I guess. Nevertheless there is something a bit post nuclear meltdown about these beasties. I put them into a modified version of Pierneef’s Hartebeespoort Dam painting and called it “Pelindabadiere.”

Once a year, former academic Leon Strydom hitches a trailer to his Citroen panel van and sets off to visit artist’s studios all over the country. Leon owns the Strydom Gallery in George. Although George isn’t exactly known as an art buyer’s destination, artists tend to respond to Mr Strydom’s dedication and he comes back from his travels with a load of work that makes up his annual Summer Show. So this week I got sidetracked into a flurry of paper staining and made some work for him, even though I should be putting them in the box marked “Solo show, Stellenbosch University Art Gallery, May 2011” Which is sooner than anybody thinks!

German painter Casper Friedrich (1774 -1840), was a contemporary of JMW Turner and friend of Goethe. His solitary figures peer into the landscape, inviting us into their world of melancholia and awe. Rather than painting traditional religious subjects, Friedrich depicts the encounter with landscape. It’s no accident that these works emerged as Europe industrialised and the Church weakened. They compensated for the loss of both Nature and God. I don’t know if the godless philosopher Nietzsche (1844 – 1900) ever saw Friedrich’s work, but the solitary mountain wanderer would surely have approved of it.

In the Jura region of France, another lone mountain man and painter was jotting down his sensations: “The clear green streams wind along their well-known beds; and under the dark quietness of the undisturbed pines there spring up such company of joyful flowers as I know not the like of among all the blessings of the earth”. John Ruskin (1819 – 1900) was England’s most influential Victorian art critic. He churned out volumes of impenetrable but poetic writing. He hated the demolition of old buildings. He disliked mountaineers. He didn’t like the march of Progress.

But the flower lover was no hippy: “My continual aim has been to show the eternal superiority of some men to others … and to show also the advisability of appointing such persons to guide, lead, or even to compel and subdue their inferiors, according to their better knowledge and wiser will.”

Ruskin as an Imperialist. Oil on canvas(2005)

Left at Uniondale and to Knysna via the fabled Prince Alfred pass. Another one of Uberpassbuilder Thomas Bain’s creations, the pass was built in 1867 and is 80k of dirt snaking through the majestic Outeniqua Mountains. I don’t know if Oom Henk took this path on his way to paint the Knysna Heads, but he should have. It’s wild, in an Alpine kind of way. Very…um….German.

Pierneef was the son of a Dutch immigrant to Paul Kruger’s Transvaal Republic. He spent some of his school years in Holland, and visited Europe again in 1925. He was influenced by Art Nouveau and there are links to Piet Mondrian in the flatness and simplification of planes (and the obsessive renderings of trees). You can place him in the tradition of Northern European Romanicism. While the Francophone painters of the South sought to capture the passing moment, the depressed Northern painters looked to the landscape for something lasting and transcendental. This often involved intense almost scientific study of botany and geology.

After an hour of driving in honeyed afternoon light, you get into the belt of Knysna forest and the tall trees loom. I’m dozing now, tired out by all this beauty. Right at the end of the pass, some wit has left a message:

A little trip up to Jo’burg is one of the reasons why I haven’t been posting. The other is that while I was there I got a rash from hell that drove me to distraction. Apparently it’s common practice for bloggers to post their rashes, but I’ll spare you that. In Jo’burg I met a photographer called Monique Pelser, and she too has been photographing the Pierneef sites. Which goes to prove that if you have an idea, you can be sure someone else is having it at exactly the same time. Monique tells me the Pierneef museum is moving to Stellenbosch. I’m trying to confirm.

If you are ever in Graaff Reinet, the taxidermist across the way from the Pierneef Museum is worth a look. They keep the main door closed though, as if to discourage casual enquiries or bunny huggers:

I also encountered this bloke, who makes finely crafted greeting cards out of beads and wire.

He has a congratulatory sales technique: “Well done, I’m proud of you,” he says when you buy a card. He asked me “Are you the Big Man, the one who is going to place a Big Order?” No, actually china I’m looking for the Big Man myself .

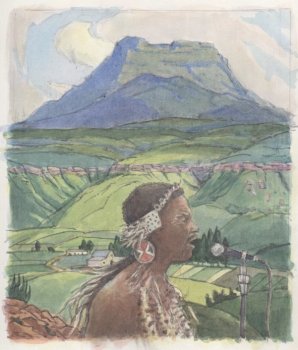

Back up to the Valley the next day, but this time I stay further back in order to get the long view. You can park here and walk up to view Spandau Kop. To the right is the Valley. You also may find paragliders launching themselves into the afternoon thermals.

There’s a kind of a contrast between Pierneef’s foreboding stone columns and the jauntines with which they throw themselves into the air. Pierneef’s painting demands that we regard God’s handiwork with reverence and awe. We are put in our place by the monumentality of the forms. And here we are in the 21st century, treating nature as our playground. But this has none of the intrusiveness of, say, quadbiking – there’s a graceful loop through the air. The view from up there must be awesome. I’d love to do it.

Walking a bit off the road and a bit closer, I seem to be in the right place. The shadows on the original painting tell us there was an afternoon light falling on those stone pillars My little watercolour also picks up on that yellowish sky. Pierneef obviously had a lot of confidence in his working drawings as well as his colour notes. Again, they seem very accurate. And he’s made a very good job of imposing order on that chaotic jumble of rocks and vegetation at the bottom of the valley. As the shadows lengthen, I suddenly notice the expanse of space to my left. It’s vast, but stitching together a number of photographs, it’s paintable. That’s my version of the Valley of Desolation

My little watercolour also picks up on that yellowish sky. Pierneef obviously had a lot of confidence in his working drawings as well as his colour notes. Again, they seem very accurate. And he’s made a very good job of imposing order on that chaotic jumble of rocks and vegetation at the bottom of the valley. As the shadows lengthen, I suddenly notice the expanse of space to my left. It’s vast, but stitching together a number of photographs, it’s paintable. That’s my version of the Valley of Desolation

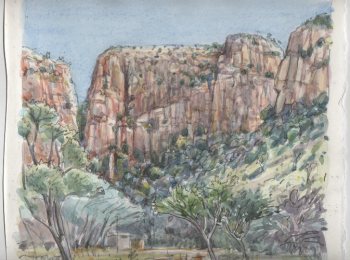

The Valley of Desolation. I’ve been here before, and not quite figured out where our man painted it from. The original seems to have been done from the bottom of the valley, but there’s no easy way down there.

Did Pierneef really trundle all the way to the bottom? He was more inclined to stop the car on the side of the road, in my experience. Surely I won’t have to drag my creaking old bones down there? Maybe he was slightly down from the top? I keep on up to the top and, heading off the designated footpaths, try to get lower down. Earlier, there were some fuckwits on a team building exercise, but they’ve moved off. It’s a weekday. It’s dead quiet. I’ve got the whole frightening vast clump of stones to myself.

It’s a warm, still winter’s day, a kind of perfection for the outdoor painter, and I start drawing right away. But I’ve taken too long to get here, and I’m not really in the right place. There are non specific little fears niggling around my brain, the kind of stuff that gets thrown up when you can’t help noticing your own insignificance in the face of geological time and measure. Absurdly, I try to downscale all of this onto an A4 sketch pad. And I make a note underneath. It says: ” certain primordial fears; fear of heights; fear of dehydration, fear of dying alone, etc….”

Back up the pass from Prince Albert now, sketchbook in hand. On both sides of the road there are outrageous rock formations, shaped by mighty forces:

I get to the site around 12.30 and settle in. A lot of the sites I’ve been to have changed since Pierneef painted them, the landscape encroached upon by highways or housing. But this is unchanged since Thomas Bain and his crew hammered their way through here in 1886. The year of Pierneef’s birth. (And Johannesburg’s too)

But the gravel road is showing the wear and tear of fairly high traffic volumes, so while I’m doing the watercolour I make a list of the passing traffic: Fortuner, Isuzu, Land Rover, Toyota sedan, 2 cyclists, Suzuki, Bakkie, two Dutch people in a small car, Correctional Services Toyota, Poephol in a Prado, CA Yaris, Silver merc, Silver Toyota, White Toyota, 2 cyclists at speed, Landcruiser, Party of 8 cyclists, Isuzu bakkie van Bredasdorp, Kia, Colt with a Staffie, Big yellow truck (12.30 – 4.30pm). The cyclists, by the way, had pedalled over from the Oudtshoorn side and after spending the night in PA were coming back over the next day. Eina.

So there’s no site. But I’ve got a tea date with George and Sheila Coutouvidis and I start the downhill glide. Its 20 kilometres of downhill all the way to Prince Albert. I took the bicycle ride down a few years ago. You pay a guy in PA to take you up in his shiny Toyota. {Make sure your bike brakes are in good working order.}

This is what I’m looking for:

It’s not one of his best panels. We get a sense of the size of the mountains, but there’s no drama here somehow. There’s a lack of illumination, no light source. The key to finding the site is the road of course. It curves around two hills, and there’s a hint of a river just off to the right. I’m halfway down the pass already and I happen to glance to my right and there it is:

I stop the car and let out a yell (as one does when finding a Pierneef site.) I’m in exactly the right spot. It’s about 3.30pm and there’s no direct sunlight anymore. That explains the lack of light too. Fantastic. But now I’ve got to go and have tea with George and Sheila. (Double click the pic and you should be able to see the second curve of the road clearly.)

Three years ago I looked on the North side of the Swartberg Pass for the Pierneef site – nothing doing. Its definitely on the south, or Oudtshoorn, side. I take a farm road. No traffic, no cell reception, not much of a road. Probably pretty much how it was for Pierneef in the 30’s.

You take it slowly on a dirt road, and that makes you look at where you are. I’m looking at some pretty big mountains, feeling suitably insignificant. I’m sure I’ll find the site near the bottom of the pass, but I don’t. I do a watercolour and carry on up. There’s nothing that looks vaguely like the place I’m looking for, but the Pass is stunning, something new around every corner. Quite near the top I have something to eat and do another watercolour, then head to the top. There’s a fierce wind , so I stay in the car and do a third little watercolour sketch.

There’s nothing that looks vaguely like the place I’m looking for, but the Pass is stunning, something new around every corner. Quite near the top I have something to eat and do another watercolour, then head to the top. There’s a fierce wind , so I stay in the car and do a third little watercolour sketch.

OK. I’ve got a page of watercolours but no idea where the site is. Perhaps he made it up?

From De Rust you cross Spookdrif, Skansdrif, Damdrif, Boesmansdrif, Skelmkloofdrif, Aalwyndrif, Nooiensboomdrif and there it is, Dubbele Drif se draai:

Following the curve of the road, this is the right place. It seems as if the river’s on the right, but if you look closely its running onto the road from the left. The river now runs under the road. And that large boulder is indeed there. Because of the new bridge, I can’t get as close as he was, so the cliffs seem less towering. The light coming in from the east tells me he was here early on a summer morning. At this time of year it only gets a touch of late afternoon light.

I’m glad that the decision about what to paint in the Poort has already been made for me, because there’s a bewildering majesty to this place and I wouldn’t know where to start. But that thing I said about the silence isn’t strictly true. There are quite a few big trucks winding through here. And some of them like to hoot at the weird oke in the hat painting next to the road, which makes me jump.

Way down there in Hermanus the rain and cold is coming in and on the R62 it’s light and warm and cloudless and I can feel my winter coastal depression lifting as the road winds ahead.

In De Rust in the late afternoon there’s a donkey cart clattering down the main road. A tiny khoisan woman bearing a large pumpkin comes down the hill and tries to sell it to me. She’s lurching a bit, not only from the weight of the pumpkin. There’s a bloke hovering in the background. The pumpkin is the best thing that’s happened for some time, and its probably going to end badly. Slightly unsettled by this reminder of the abject state of our first people, I meet Hermann’s son Thomas and his American grandparents. They like the Klein Karoo, are puzzled by the ‘German speaking brown people’, and have an unnecessary fear of encountering a Cape Cobra.

In De Rust in the late afternoon there’s a donkey cart clattering down the main road. A tiny khoisan woman bearing a large pumpkin comes down the hill and tries to sell it to me. She’s lurching a bit, not only from the weight of the pumpkin. There’s a bloke hovering in the background. The pumpkin is the best thing that’s happened for some time, and its probably going to end badly. Slightly unsettled by this reminder of the abject state of our first people, I meet Hermann’s son Thomas and his American grandparents. They like the Klein Karoo, are puzzled by the ‘German speaking brown people’, and have an unnecessary fear of encountering a Cape Cobra.

(Double clicking on any photograph gets you an enlarged version)

Over the mountains to De Rust tomorrow to pay my respects to famille Niebuhr. Then into nearby Meiringspoort, watercolours at the ready.

Don’t worry, I’ve got another block of Quinacridone Red (top right).

If I find an internet cafe in De Rust, dear Reader, I shall make a posting or two. Otherwise see you in about twelve days time….

I leave you in the good hands of this fellow traveler

With our blogger’s computer ostensibly fixed, some pics of the recce to Stellenbosch. What I was looking for:

Driving into the town from the south the mountains were curiously shy, even absent. I ended up in the dorp itself, dodging Sunday morning churchgoers and Dylan Lewis cheetahs. Eventually I sniffed out the yellow leafed road to Jonkershoek. That’s where the mountain is:

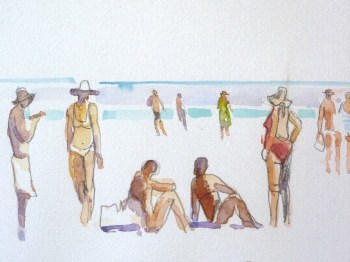

I kept on up the valley and at the end there were many cyclists and a nature reserve. I was too close to the mountain by now, but did this watercolour anyway. Its not very good but hell it was lekker up there in the Autumn sunlight.

Not Valentines day, but Nineteenth Century Romanticism. The Romantic painters responded to the industrial age by looking for the sublime in Nature, a quest that was both aesthetic and spiritual. And even well into the C19th, when the Impressionists were drenching themselves in sunlight, the gloomy Northern Romantic tradition continued. (It’s been argued that Pierneef belongs to this current in European painting.)

I chose to show the harbour buildings overwhelmed by the magnitude of an Atlantic storm: A very Romantic idea.

Oil on canvas.60cm x 170cm.2009

What emerged out of that was the recolouration I’d been hoping for (you don’t quite know what it is, but you recognise it when you see it.) I also lost some lekker paintings within paintings

Then there was the small matter of The Sea, the dreaded sea. After numerous false starts I remembered Anton Chapman‘s advice about putting down a base of deep red. He has painted a lot of sea and knows his stuff. A layer of Venetian Red and some editing decisions later:

And after quite a bit more tweaking:

The beast is laid to rest at last.

I finally figured that JHP was down by the docks – at something called Berth A. After wheedling my way past security, I felt sure this was the site: a view across the water of Lion’s Head with some industrial buildings in the foreground. Back in the studio I started rendering the panorama in a fairly loose but literal kind of way, laying in the details happily unaware that I was about to ambushed by a whole range of dubious characters….